My experience making a chess engine

Goals

First things first, what do I want to accomplish with my engine? There’s an endless amount of algorithms, strategies, and methods I could implement but I’ve got to know where I should say “alright, it’s done.” (This is something I struggle with sometimes, if you couldn’t tell)

Here’s what I want my engine to be capable of:

- Generating all possible legal moves quickly

- Redoing and undoing moves

- Handle complex moves (promotions, en passant, castling)

- Load FEN strings and algebraic notation

- Handle user input, display graphics

In addition, the chess engine will also have an AI that will use a minimax algorithm to search for the best legal move given a position and side. As a skill target, I want it to at least be able to beat everyone at my high school’s chess club.

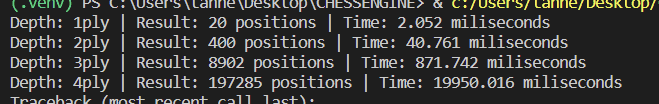

First Python Version

My first rendition of this project was in Python. I used PyGame to render the graphics, however I quickly began to regret my choice of language. Chess engines require lots of bit manipulation, and having integers, floats, and bits abstracted away made things very difficult. More importantly, it was extremely slow. Here’s the results of something called a “perft test,” which essentially measures how long it takes to generate all legal moves by looking a certain depth into the future. For reference, my benchmark for a depth of 4 was around 500 ms.

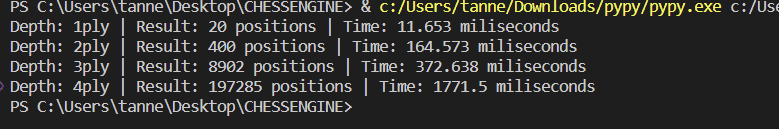

I attempted speeding up the engine by changing the interpreter to pypy, which required very little change of the codebase. While it was a significant speed up, it was still nowhere near where it needed to be to make a good chess engine.

By now, I was significantly demotivated and considered quitting the project. I did some research online and found similar issues with other engines written in Python. Many users suggested writing engines in C++, Rust, or Java. I decided to port all my work over to Java since I was already taking an object oriented approach and I had some experience with it.

Java Foundation

With my eyes set on a new language, I begin converting everything over and making minor improvements where necessary. I used JavaFX to render the user interface. The biggest challenge was converting all the python lists to strict types in Java because I had to differentiate between lists that had adjustable size and ones that were a fixed size.

With Java’s strict types, I was able to implement a Bitboard class. A Bitboard is essentially just an unsigned long integer, with each bit of the 64 bits representing a square on the board. It’s extremely useful when writing fast move generators since bitwise operations are inexpensive. I also represented the pieces and moves as bits, by reserving certain parts to different elements. For example, a piece was represented by 4 bits that reflected the piece type and another bit to determine color. Overall, this had a very dramatic increase in speed that I was fairly satisfied with.

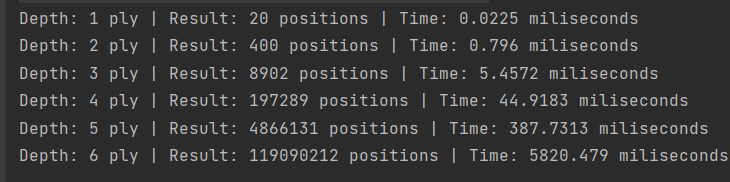

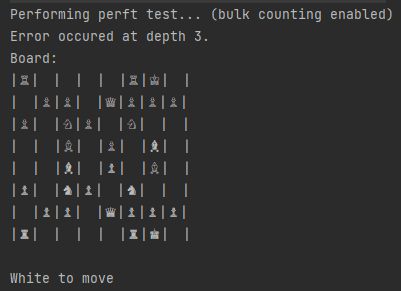

Debugging Move Generation

The move generation was fast, but it wasn’t always right. Nobody can write perfect code the first time around, and that includes me. To find exactly where the engine was going wrong, I wrote a debug catcher that found the exact position and all the moves that led up to it that caused particular errors. Using the perft test, I could easily let the engine search through millions of positions and see if an error crops up. Issues that don’t cause an error will also be detected by discrepancies in the number of positions counted at certain depths. The Chess Programming Wiki provides a great resource that lists out positions that are specifically designed to root out common problems in chess engines.

| Example of the debug output | ”Position 3” from Chessprogramming.org |

|---|---|

|  |

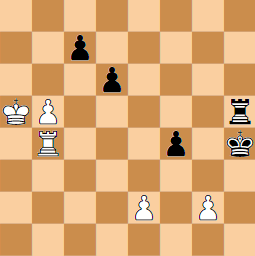

The image on the right reveals an example of a position that caught me off guard. Black’s leftmost pawn is able to jump two spaces, which creates the opportunity for white’s pawn to capture back with en passant. However, the black rook is pinning the white pawn, thereby making it an illegal move. The reason it’s tricky is because the program thinks the black pawn is blocking. The solution was to add special logic for en passant, since it’s the only move where the piece doesn’t move to the position of the piece that it captures.

Creating the AI

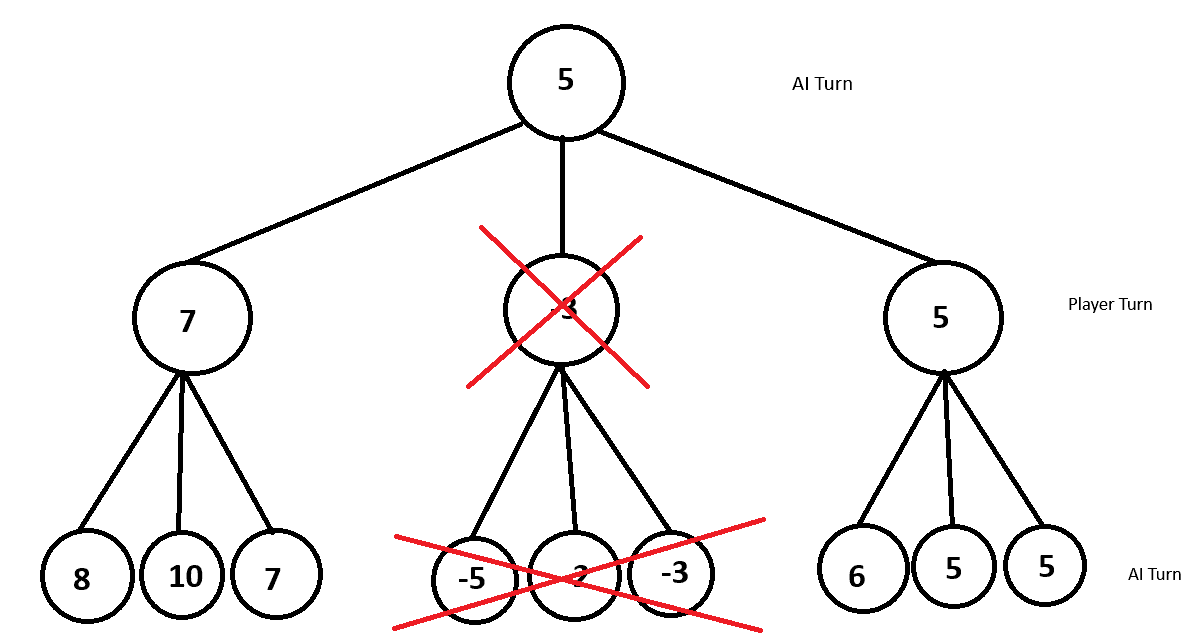

With all the primary goals of the chess engine met, I started work on the AI. I began with a very simple minimax algorithm that explores every legal move the AI can make, then explores all the options the AI has after that move, so on and so forth to a designated number of moves into the future. The problem is that the number of moves the AI has to look at increases factorially with n depth. A clever way to reduce this is through the alpha-beta pruning algorithm.

In the image above, the AI is exploring 3 possible moves it could play for the next turn. The moves are scored by how much of an advantage the AI has at that position. The current advantage is 5 points. From right to left, the first option is 5. It searches all the moves that come after that. Once it’s done, it moves on to the second option which is -3. Since -3 is so much worse than 5, it shouldn’t bother searching for possible moves after that because it’ll be a waste of time, so it “prunes” that branch of the search tree.

One interesting quirk of this optimization is that it depends on how the moves are ordered. For example, if the move that scores 5 was after -3, the AI would’ve searched through the -3 branch anyways because it doesn’t know there’s a better branch yet. Taking advantage of this, the AI can sort the moves early by guessing which ones will probably give it a big advantage. Checks, captures, castling, pawn promotions, pins, etc. are moves that can have a much larger impact on the game than regular moves. By sorting the moves this way, more branches will be pruned and the AI will be decently faster.

Improving the AI

While the AI does play better than random, it’s still quite stupid at this point. The bot’s openings often involve bringing out the knight then shifting the rook back and forth until the opponent begins threatening the position. The bot is suffering from the “horizon effect.” It searches until a particular n moves into the future, then evaluates that position and calls it a day. Perhaps a queen captured a pawn, giving a material advantage to the bot, but that pawn was actually defended by a knight and the queen is lost on the next move which the bot doesn’t look ahead to.

The solution is a “quiescence” search, a search identical to the minimax algorithm that only looks at threatening moves, such as captures, promotions, and checks. This prevents the aforementioned situation from arising and makes the bot play far more legitimate moves. The “quiescence” search doesn’t have a predetermined number of moves to search in the future. Rather, it stops once there are no more threatening moves remaining. This adds an element of unpredictability to the length of the AI’s search, but the benefits far outweigh the downsides.

After the quiescence search implementation, the AI does occasionally beat some of the newer members of my chess club, but unfortunately struggles with its veterans. The middlegame is decent, but the opening moves and endgame leave a lot to be desired.

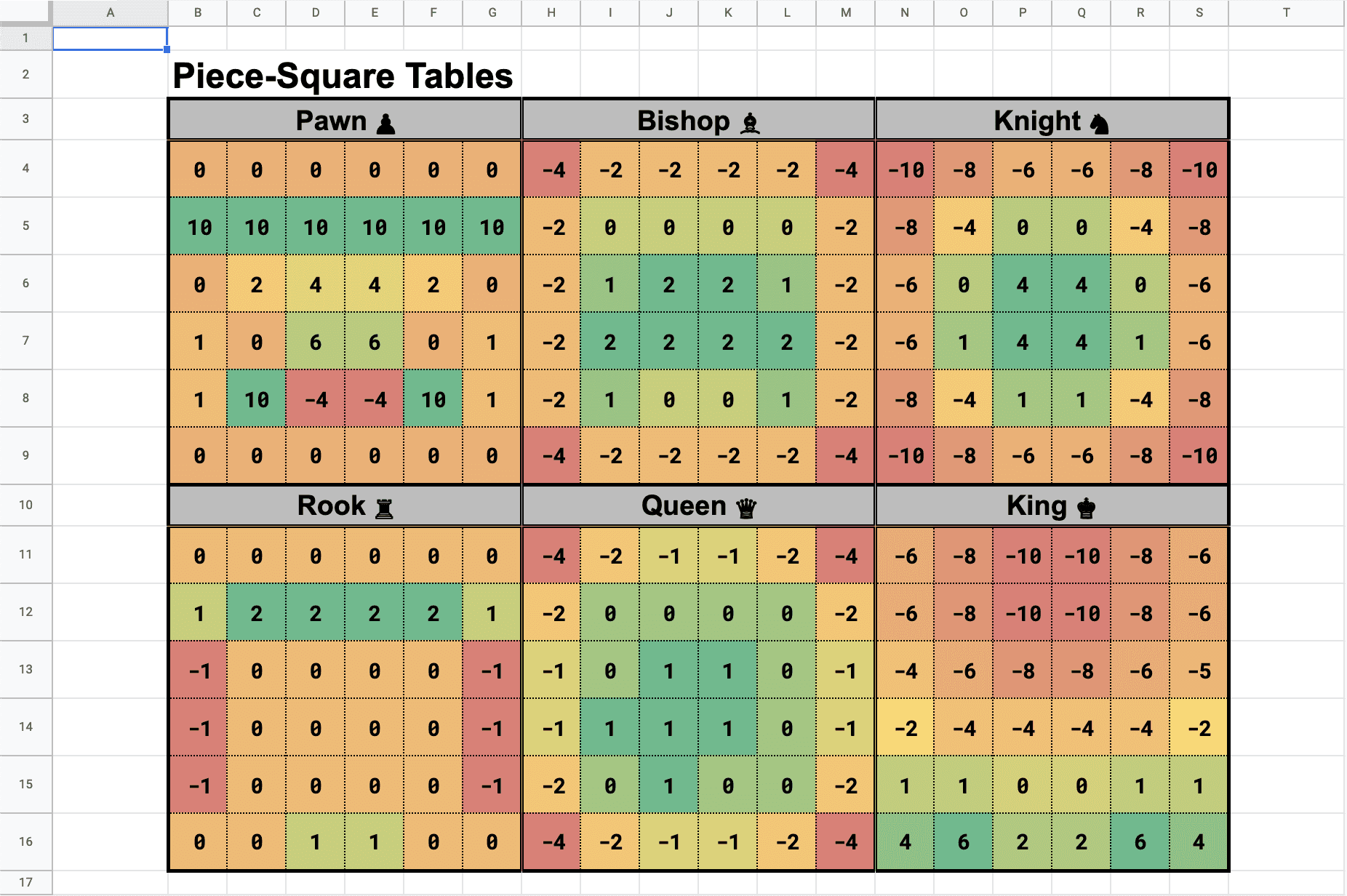

For the opening, a good idea is to add piece-square tables, which are essentially predetermined “bonuses” given to certain squares of the board depending on the piece. For example, knights and pawns are encouraged to take the center while the king is encouraged to hide in the corners. Figure 7 shows some of the tables that inspired the ones I used for my own engine.

For the endgame, the applicability of the piece-square tables diminishes, so the bonuses they give are reduced when the game is nearing an end.

The bot is definitely better at openings, but the endgames are still hopeless. The most important factor of winning an endgame is understanding pawn structure and king position. Generally speaking, the closer a king is to the edge of the board, the easier it will be to deliver a checkmate. As the game nears an end, the AI calculates a bonus whenever a move forces a king towards the edge of the board. It also encourages the kings to get close to each other to protect any pawns. This is a dramatic improvement to the endgame capabilities of the bot, and since there are fewer pieces, the bot can look farther into the future within the same time frame.

Results

After much ridicule from my friends at the chess club, my little bot was about to show them the power of technology. I handed it off to the teacher and other members—victory after victory rolled in. It was glorious.

The bot’s openings still weren’t great, but it was far better than shuffling the rook. It tended to be far too aggressive with the queen, which could be easily punished by the opponent by repeatedly attacking the queen while developing pieces. The middlegame is where it excelled. It outmaneuvered and chipped away at the enemy position. The only issue is that it struggles with understanding pawn structure. It had no trouble with double, sometimes triple stacking pawns and leaving others “isolated” (meaning there are no pawns at its side to support it). That meant that if it failed to outmaneuver in the middle game, it tended to set itself up for a very difficult endgame. However, if it had even a small material advantage, it usually could come out on top.

Future plans

A feature I want to implement that’d be relatively easy would be having precalculated opening playbooks stored. Within the first few moves, if it finds the current position in a large collection of openings, it follows the opening instead of trying to calculate a move itself. This would diversify the openings of the bot and hopefully prevent the overly-aggressive queen issue.

Another big addition would be transposition tables. Whenever a position is evaluated, it stores the position in a huge lookup table for any future scenarios, so when the bot encounters that position again, it doesn’t need to run the same calculations. This is a fairly difficult feature to add though, as the only way to make it effective is by using a hashing algorithm like Zobrist hashing.

Many modern chess engines have an understanding of pawn structure. They give bonuses for when pawns are defending each other, and punish for stacking pawns and not protecting the king. This would be a great addition against tougher opponents who may be able to take advantage of poor structure towards the endgame.