The impact of the automobile on American cities

The frustrating feeling of being stuck behind a line of cars at a red light is almost universal to Americans. Every red light seems to be followed by another, and the constant hum of engines and the dance of brake lights have become familiar companions. Over the decades following the 1960s, the daily commute for most Americans turned from walking and public transit to personal vehicles. In modern times, for many residents of the suburbs, walking to stores or restaurants from the home is rare if not never. Cars, with their heating and cooling systems, music players, and independence grant an unparalleled level of convenience—but what is the cost of this convenience, and with all this traffic, is it really convenient in the first place? Urban design and infrastructure in American cities is focused on facilitating unsustainable car travel, which has led to scars of racial segregation, declining neglected downtowns, ever-growing traffic, deaths in automobile accidents, and detrimental environmental effects. Instead, shifting towards public transportation, denser mixed-use housing, and better-funded and equipped public transportation networks such that every individual does not need to own a personal vehicle will create more sustainable and diverse urban environments.

It’s important to establish that both the design of American cities and the lifestyle of Americans is focused on facilitating personal automobile travel. A 2016 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) establishes that “[t]he United States is highly dependent on transportation by personal vehicle,” as there are “1.2 vehicles per licensed driver and 2.1 vehicles per household in the United States” in 2014 (Baldwin et al. 675). This means that there are more registered cars than people who can actually drive them. On its own, this statistic isn’t remarkable, but the effect it has on the design of American cities is. Cars spent a majority of their lifetimes not moving—that’s a lot of room being taken up. Not only do cars need space at home, but they also need space both at and towards the destination. All this space ends up making American cities very spread out, often putting destinations and commutes “generally beyond walking distance” (Handy 4).

The large amounts of space required by cars make our cities hostile to pedestrians.

However, owning a vehicle doesn’t necessarily mean it’s the only way to get around. If walking is out of the question, one can always take public transit. That’s true, but in “the suburban areas of metropolitan regions,” the most ubiquitous zoning type by far, “transit service is relatively sparse, leaving residents with no option but to drive” (Handy 5). This explains the initial statistic: destinations are too far because of cars, so Americans are forced to use cars to get to the destination. But cars are a relatively modern conception compared to most of American history. It’s important to emphasize that universal car ownership was a desire born from the American lifestyle rather than a need born from the nature of American cities. Since the days of the western frontier, Americans have always loved personal freedom, and the personal vehicle is the perfect embodiment. Implicit in this lifestyle choice is that Americans believe they “have the right to drive anywhere they want at any time of day they want at speeds unimpeded by congestion,” as congestion is “a threat to personal freedom” (Handy 23). Through the eyes of the American public, if the government fails to keep traffic low and roads maintained, they are purposefully restricting the mobility and freedom of the American through mismanagement of tax funds. Thus, this has become the ultimate driving force behind continued investment in road infrastructure.

It’s clear American cities are designed around the car, but as long as road infrastructure keeps up with demand, it’s difficult to see any particular problem with this urban design methodology. But behind the curtain, road infrastructure is not keeping up with demand, automobile deaths per capita in America have exceeded that of other developed, post-industrial countries, and individuals not suited to drive are forced behind the steering wheel. Handy has noted “beyond doubt” through numerous statistics that “vehicle travel has grown faster than highway capacity, population, the economy, or just about any other possible causal factor” (Handy 8). In other words, America’s traffic problem will just continue to get worse and worse as cities continue to sprawl. Moreover, besides some very obvious environmental consequences, car-centric infrastructure also forces everyone who wants to contribute to the economy behind the wheel. For example, consider how an inebriated man will get home. If he is responsible, he will call a taxi, an Uber, walk, or take transit. However, some will rather hedge their bets behind the wheel than deal with the difficulty of those options. This trend is outlined by numerous studies: between 2000 and 2013, when “[c]ompared with 19 other high-income countries,” particularly countries in Europe where transit is more accessible, the U.S. has “the most motor vehicle crash deaths per 100,000” and “the second highest percentage of deaths related to alcohol impairment” (Baldwin et al. 674). The first statistic also points to another important fact. It’s not just intoxicated individuals who aren’t suited to drive. The elderly, the disabled, people who are just generally poor drivers. Compared to driver’s tests in Europe, the U.S. is very lenient with handing out driver’s licenses. But, it’s silly to put poor drivers at fault for trends in automobile deaths—this is the consequence of poor foresight by early urban designers.

U.S. Pedestrian Deaths Hit Highest Level In 30 Years. Pulled from Statista.

These consequences were not seen by early urban designs in the 60s, as mass movement into suburbs created a sudden demand for car infrastructure. This led to rampant and careless interstate and road construction and the deterioration of the urban centers of many American cities. The mass movement was fuelled by the undesirable nature of the city to middle class white families. Suburbs—low density, single-family homes that sit on the outskirts of the city—became the perfect home. They exploded in popularity and were built at unprecedented rates. The issue facing urban designers at the time was finding a way to transport workers from the suburbs to the downtown business districts. The solution was clear: the automobile, the “beneficent liberator of urban dwellers from the cramped confines of the industrial city” (qtd. Brinkman and Lin 82). To note, there is nothing wrong with having highways circle around a city—the issue arises when they cut through them. The future of transportation was envisioned as massive 3-lane elevated highways that cut through dirty city streets. However, this future came at a cost—a cost that far outweighed the benefits. For one, urban highways “chop cities into pieces, creating disconnected zones, isolating people from business districts and often from urban waterfronts,” (Roberts 1), leading to industrial and commercial decline as buildings have to be bulldozed to make way. Remaining buildings experience a sudden decline in customers, employees, and land value as nobody wants to live, work, or shop near noisy, polluted concrete megastructures. This created a sort of positive feedback loop, as suburbs led to more interstate construction, which made downtown regions more undesirable, which led to more people fleeing to the suburbs. A recent 2020 study noticed that sudden declines in urban regions throughout the 60s and 70s were primarily focused around regions with freeways cutting through them. They reasonably concluded that “a significant part of the decline of U.S. central cities was due to lower quality-of-life in central neighborhoods following the construction of urban interstates” (Brinkman and Lin 84). There was significant resistance to this explosion of freeway construction, but “protestors had little power to stop freeway planners” (Brinkman and Lin 82). By the time legislation was passed requiring more careful consideration of freeway construction, many of the routes were already planned or partially constructed. However, despite all the things they ignored, one thing that was especially considered by these freeway planners were what neighborhoods specifically these freeways ran through.

Throughout the 60s, there were mass protests against freeway construction.

This sudden expansion of freeways and road networks came at the cost of poorer, particularly African American neighborhoods, as racially prejudiced urban designers intentionally drove highways through urban ghettos and utilized the expensive nature of the personal automobile to purposefully restrict the mobility of impoverished residents. The war’s demand for labor had caused an immense migration of African Americans from the south to the industrious north. This created new black neighborhoods that lived near the economic centers of cities. Once G.I.s began returning home and starting families, they chose to move into the aforementioned suburbs to avoid minority populations in a process known as “white flight.” These white neighborhoods used any means necessary to prevent any minorities from moving in near or having easy access to the neighborhood. Since owning a car is very expensive, “low-income people and people of color often rely more heavily on public transportation than people from other groups” (Schindler 1961). So, one of the first ways urban designers “protected” white neighborhoods was by intentionally displacing transit stops. Another way ties into those aforementioned urban highways. Although they were constructed with the apparent intention of “mak[ing] places more accessible to cars, it was always done with an eye towards eliminating alleged slums and blight in city centers” (Schindler 1966) and to “reshape the physical and racial landscapes of the postwar American city” (qtd. Schindler 1966). This process was so ubiquitous that it earned a slogan: “white roads through black bedrooms.” This systematic yet concealed destruction is not some historical tragedy—it’s still a hugely significant part of modern American cities. Huge elevated or sunken interstates criss-cross cities like shattered glass, splitting affluent neighborhoods from impoverished often minority neighborhoods.

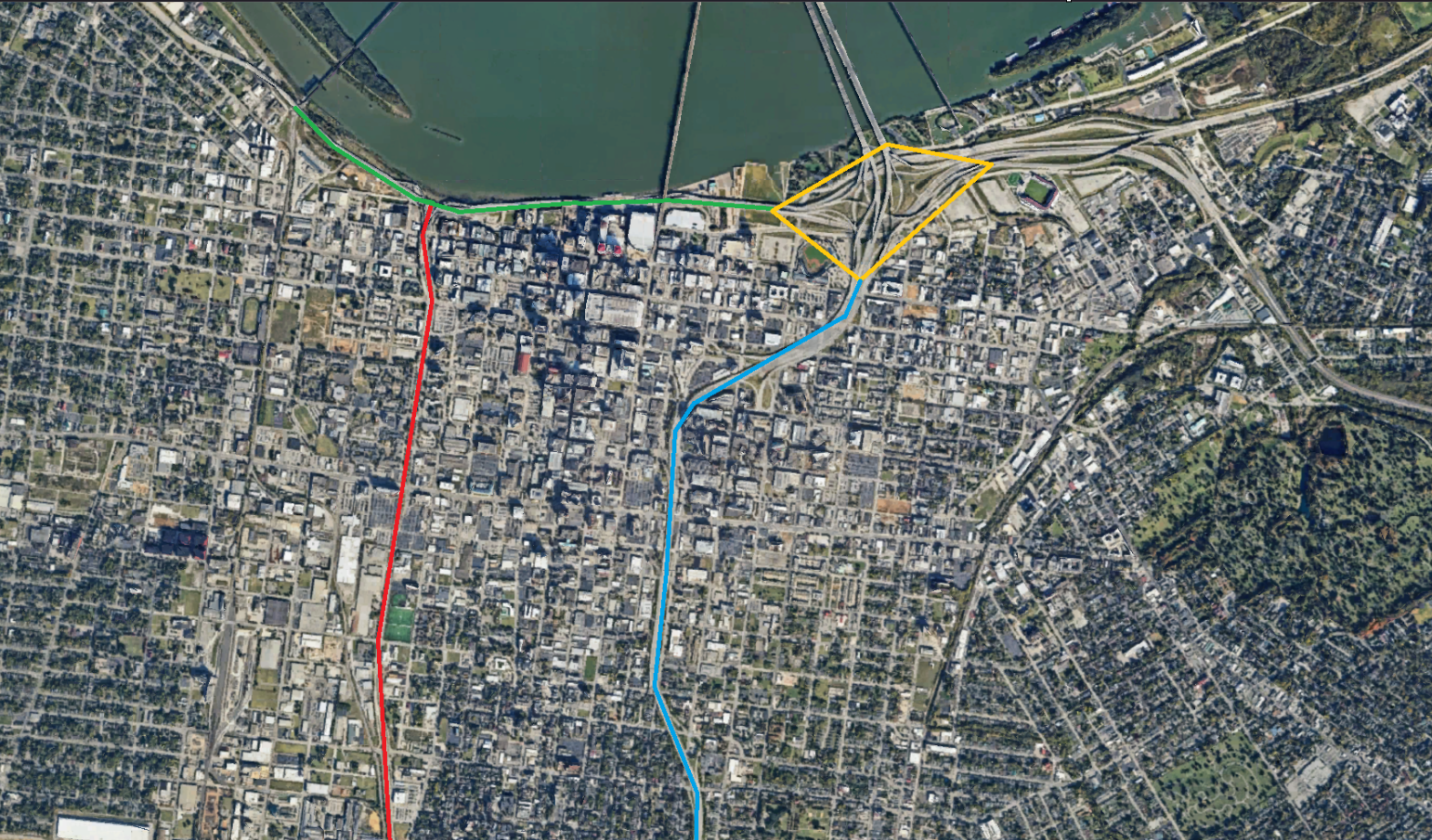

One example of this racially-motivated urban decline is my city, Louisville. Once a sprawling industrial city, the areas surrounding the central business district were converted into ugly urban highways, multi-lane roads, and giant empty surface parking lots which created a physical divide between the poor African American west and the richer white east. Louisville was primed for the industrial revolution. Located on the Ohio river, it sits as a connection between the east, the south, and the midwest. Industrialization turned the city from a small town to a huge, bustling metropolis. However, after the war, the city underwent a “urban renewal” plan to bring the city into the new age of the automobile. This involved bulldozing “large swaths of Louisville’s Downtown” to make way for “acres of asphalt surface parking lots and generic, bland buildings” (Klayko 3). These cracked parking lots are ugly scars on a once bustling downtown that produce no tax revenue as they remain mostly empty, even on weekends. They are largely a result of parking requirements for buildings, as the government punished businesses and offices that didn’t create enough parking spots for their expected amount of visitors. The racial aspect is prevalent too, as a “vibrant African American district” along Muhammad Ali Boulevard “was bulldozed and leveled creating a canyon that exacerbates Louisville’s so-called Ninth Street Divide” (Klayko 3). The Ninth Street Divide was a physical road barrier made to separate the downtown central business district from the poorer African American neighborhoods in the west. This division still exists today and makes it difficult for people living in these areas to access employment downtown. Last but certainly not least, the urban highways discussed earlier are ever present in Louisville. Three highways—I-64, I-65, and I-71—smash into the city’s center, splitting up the affluent suburbs of the east from the south and west. The downtown itself is cut in half by I-65 and the waterfront west of downtown is completely cut off by I-64. In the east, there is a waterfront park, but it is desperately choked by a huge stack interchange colloquially called Spaghetti junction. The junction and surrounding highways were recently expanded by the local government, causing lots of trees to be cut down and businesses to be bulldozed. Clearly, modern American cities like Louisville have been and continue to head in the wrong direction towards an inherently unsustainable model of urban development.

This is a map of my city, Louisville. The 6th street divide is highlighted in red, I-64 in green, the Kennedy interchange in yellow, and I-65 in blue.

Besides the destruction it has caused to urban centers, car-centric infrastructure is unsustainable, both economically and environmentally. Any attempts to expand existing road infrastructure to facilitate new traffic has been proven repeatedly to cause more traffic, in a counter-intuitive phenomenon called induced demand. Whenever a road is expanded to handle more capacity, that “new road capacity generates an increase in travel beyond any increases generated by new development” (Handy 7). In other words, whenever a road is expanded, the increased potential for traffic brings in new developments, whether it be homes, stores, or offices. These new developments then fill the road back to or more often beyond its capacity, creating a new need for expansion. This is a significant representation of the unsustainability of this kind of urban expansion, not just environmentally but also economically for the city. Roads are very expensive to both build and maintain, and as those initial roads built in the 60s-80s start to reach the end of their life, cities are struggling to maintain them. However, as these roads are being rebuilt and repaved, cities across America have started to reduce the size of road networks in urban areas, known as “road diets.” As difficult and counter-intuitive induced demand is, the phenomenon also holds true for the inverse: “reduced road capacity leads to reduced traffic. If you stop inducing demand, demand falls” (David 12). The entire problem of traffic congestion will always be present unless cities stop incentivizing people to drive everywhere. However, given the existing design of American cities, this seems entirely implausible—homes have been built, roads laid—it’s not plausible to evict families and bulldoze homes for the sake of sustainable urban development.

The Katy Freeway in Houston, TX has 26 lanes in its widest spot, and it still gets congested!

Given that expansion of road networks doesn’t work, the best solution to solve congestion and revive cities to their former vitality is to rebuild within existing urban areas what was destroyed: trams, subways, trains, row housing, and mixed-use buildings. As existing suburban developments are a “great offender in sustainability terms, the main opportunity for positive action exists within the current urbanised areas … these areas offer a very high level of opportunities for urban regeneration” (Olszewski 3). Across America, the demand for suburban homes is declining and demand for revitalized areas near the center of cities is ever rising. From old buildings from the late 19th century to declining suburban developments, if they’re near the city center there’s a push to renovate these rusting buildings called “infill development.” While this has bad consequences like gentrification, it provides a far better alternative to more urban sprawl. This has proven to reduce traffic congestion because all these new higher-density developments will be within walking or cycling distance of homes, stores, and urban centers. Moreover, once these “relatively high-density, mixed-use, pedestrian-oriented development[s]” expand enough, these new regions will produce much more tax revenue, allowing the city to invest in public transportation, “capitaliz[ing] on the ability of transit to deliver large numbers of people to a particular destination and increas[ing] the numbers of people transit is likely to carry” (Handy 11). This style of urban development is very similar to what European cities follow. Three to four story mixed-use buildings dominate urban areas, and the suburbs usually consist of row housing rather than single family homes. This allows far more destinations to be within walking distance and generally ends up creating better standards of living for poorer families. Of course, it’s important to acknowledge that this can’t happen immediately. Rather, government policy can help slowly transform once-declining industrial parks and urban centers into flourishing, diverst, walkable neighborhoods.

Norton Commons is a recently developed mixed-use walkable neighborhood built in the eastern outskirts of Louisville. By no means is it ideal—to access businesses and services not offered by the small shops within the community, one still has to own a car—but it’s nevertheless an improvement over suburbia. That neighborhood is now selling homes at a resounding pace, and it is being cited across the nation as an example of innovative urban design. These solutions presented are not pie-in-the-sky pursuits. They are legitimate, practical, and proven alternatives to the unsustainable model of suburban sprawl. To an average American citizen, the methodology of urban designers seems far disconnected from everyday life. In reality, it has a profounding impact. Local legislature has control over who, what, and where things can be built, but in the end, that control is only granted by the voters. Keep up with what your local city is planning, and make sure that the places you live, work, and entertain in are built around you, the human being, and not cars.

Norton Commons is a recently developed mixed-use walkable neighborhood built in the eastern outskirts of Louisville.

Works Cited

-

Baldwin, Grant T., et al. “Vital Signs: Motor Vehicle Injury Prevention—United States and 19 Comparison Countries.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, vol. 65, no. 26, 6 July 2016. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6526e1.

-

Brinkman, Jeffrey, and Jeffrey Lin. “Early Interstate Policy and Its Effects on Central Cities.” Cityscape, vol. 22, no. 2, 2020, pp. 81–86. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26926895.

-

Handy, Susan L. “Accessibility- vs. Mobility-Enhancing Strategies for Addressing Automobile Dependence in the U.S.” UC Davis: Institute of Transportation Studies, May 2002. eScholarship, https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5kn4s4pb.

-

Klayko, Braden. “Worst: Louisville Went Crazy with the Wrecking Ball in the Name of ‘Urban Renewal.’” Broken Sidewalk, 8 Feb. 2016, https://brokensidewalk.com/2016/urban-renewal/.

-

Olszewski, Andrew. “The Impact of Transport on Urban Form.” Environment Design Guide, 2002, pp. 1–5. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26148361.

-

Roberts, David. “Louisville’s ‘Spaghetti Junction’ Is a Testament to How Cars Degrade Cities.” Vox, 5 Jan. 2017, https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2017/1/5/14143746/louisville-spaghetti-junction.

-

Schindler, Sarah. “Architectural Exclusion: Discrimination and Segregation through Physical Design of the Built Environment.” The Yale Law Journal, vol. 124, no. 6, 2015, pp. 1934–2024. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43617074.